A reMAKER explainer: What do we mean by ‘systems change’?

Introduction

As reMAKERs we talk about changing systems, not just treating symptoms.

What do we mean by that? What does anyone mean when they talk about making systemic change, and how is it different from other forms of change?

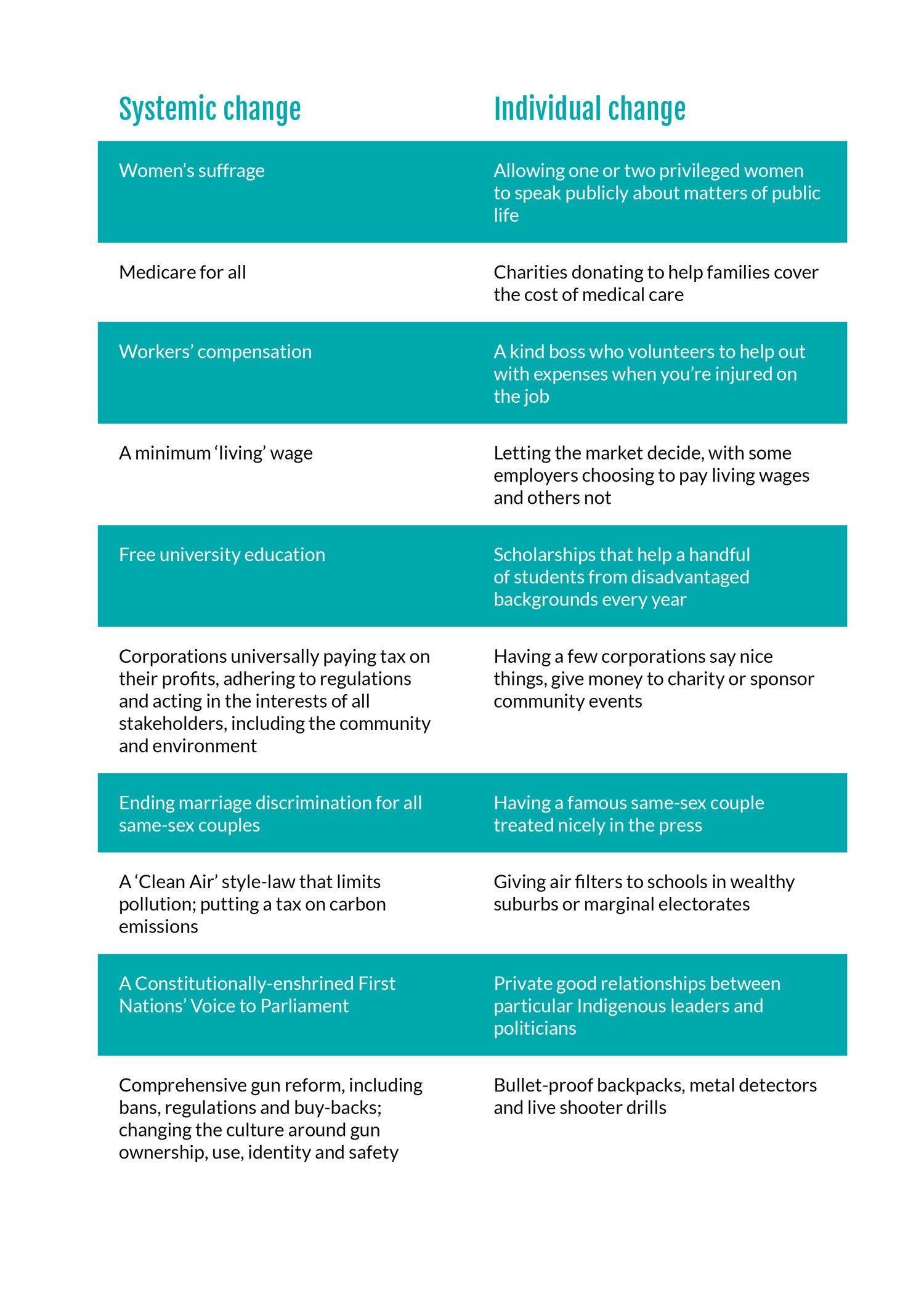

Systemic change vs individual change

“The future can’t be predicted but it can be envisioned and brought lovingly into being.” - Donella Meadows, Thinking in Systems

As reMAKERs, we believe the goal of systems-change is to always look upstream; to do all that we can as a community to ensure the makings of a good life are the rule, not the exception. To protect, perpetuate and advance the public good. To operationalise “radical love” — recognising that there is no such thing as a pain-free life: we all need compassion and care at times, support to achieve our potential, action to prevent suffering wherever possible. It is to hold the paradox that we all have responsibility for our own lives, but we do not live for ourselves alone.

Yes, we need agency. But we also need community. We are stronger together.

For the last forty years, the dominant ideology of neoliberalism has fetishised a certain market-driven, competitive individualism. We have been awash in stories of individuals doing extraordinary things. In our culture today it’s common to applaud the celebrity who donates a large sum of money to a charitable cause, the lucky audience member who wins a car or gets her mortgage paid off, the teen who triumphs over adversity. Anyone who’s spent time in America knows these stories are even more revered there (just tune into daytime talk shows if you want a taste).

These kinds of examples of individuals making a difference or succeeding against the odds are very often emotive, inspiring and popular – and for good reasons. They’re not bad or wrong. They can be useful to change systems even, by helping to shift mindsets.

However, inside a dysfunctional system that is refusing to make other kinds of changes or even acknowledge that solvable problems exist, simply lauding exceptional individuals can actually serve the dysfunction rather than the solution.

Other people’s success stories can be used to reinforce the idea that the status quo works just fine, as long as you’re worthy enough. If you are struggling or suffering, it must be because you’re not smart, hard-working, talented or otherwise deserving. Not that the systems you’re caught in might be broken, toxic, rigged or corrupt.

Of course it’s admirable to do good deeds, donate to charity, help others less fortunate and work hard to overcome one’s personal adversity. But we can’t stop there. So beware the ‘charity, not change’ narrative as discussed in our reMAKERs’ memo about the Australian bushfires. It can often manifest in sneaky, or even cuddly ways.

Changing systems, ultimately, isn’t about the lucky few who overcome the odds. It’s about the odds. It’s not about the exception, but the rule. Or to use a quote that came to the fore in discussing racism in society: ‘it’s not about the sharks, but the water.’

While individual change can still be positive and eventually contribute to wider systemic change, it’s usually a starting point at best. To flesh the difference out a bit further, here are a few practical (and somewhat simplified) examples.

In a nutshell, we are trying to do three fundamental things by changing a system:

Address problems and suffering more at the level of ‘causes’, not just ‘effects’;

Promote a lasting solution rather than interventions that will quickly dissipate or backfire; and

Shift conditions for a larger number of people rather than merely a fortunate few.

Working closer to the level of causes, not merely effects

Systems-change fundamentally seeks transformation of the problem at hand, versus merely lessening the impact of something bad, adapting to it or trying to go back to a time when things seemed better.

From racism to inequality, climate change and even covid, there’s an increasing awareness that we need to address root causes, risks and potential solutions at a structural, rather than merely individual, level.

We seek to shift systems, because unless we do, we’ll be too consumed perpetually trying to stop more bad things; rather than building more of the society, country, world we want.

Here is a primer: a top-level overview of systems and how we change them

What is a System?

The Cambridge Dictionary defines a “system” as a set of connected things or devices that operate together – whether that’s a software system, an immune system, a transport system, a political system.

So the cooling system of an engine is the collection of all the bits and pieces that have to work together in certain ways to keep your car’s engine cool. Your digestive system includes all the organs and parts of your body that break down and assimilate the nutrients in your food.

Easy enough to understand when we’re talking about discrete ‘parts’ we can objectively define, measure and observe. When it comes to the world of people and our complex interactions, it’s also useful to think about a system as ‘a way of doing things,’ such as a country’s legal system. But let’s keep it simple and take the example of your own home.

A system might include how you organise things:

Do you sort books by colour, by title, by genre, by author, by size, or not at all? How messy are things allowed to get? If you live with other people, who has responsibility for which chores? What are your guidelines around using screens? Do you have daily rituals for saying hello and goodbye? Do you eat dinner a certain way, go to bed at certain times?

All of these come together to form a kind of ‘system’ for how you run your home.

In the social sector, systems are primarily understood as a way of thinking about the world and complex problems. At the heart of any social (or human-made) system is a paradigm: a set of assumptions about how the world works and how it should work. Paradigms are not values-neutral, so people with different values and perspectives will analyse the same system differently.

For example, is the problem with our economic system that it promotes endless growth and inequality; or that it still has too many barriers to economic opportunity and penalises people for hard work?

How do we solve climate change? Is technological advancement the major answer, or do we need a major rethink of the social contract, our governing values; our relationship to nature and each other? Can we keep the market-based system that we have, but with better government policy that prices market externalities and fosters innovation?

Our answers and analysis will depend greatly on our paradigm and values.

Does systems-change mean dealing with cause, effect, or both?

Desmond Tutu once said, “There comes a point where we need to stop just pulling people out of the river. We need to go upstream and find out why they’re falling in.”

That’s about as good an argument for systems change as we’ve heard. But of course, no one is saying in the meantime that we should ignore the people drowning; sending help is certainly not pointless as far as they’re concerned!

Some of us are called to work downstream, at the level of ‘effect’ or observable event and individual intervention: our doctors and nurses, volunteers, emergency services workers, counsellors, etc. Others are called to work further upstream: our policy experts, politicians and industry leaders, economists, town planners, philosophers, activists and engineers. Many start downstream and move upstream (clinicians who go on to become government advisors, public health leaders). And many work somewhere in the middle with groups, such as our teachers and organisational team leaders. The point is that we all work together to both respond to challenges, pain and problems where we find them; and to minimise and prevent them where we can.

So we don’t have to get bogged down in the false debate between helping those hurt by the current system and changing the system itself. Often the most powerful voices for change come from those downstream, including those who’ve nearly drowned.

Our advice? Know what work is yours to do. But look around to see what else is happening, so we’re not just pulling people out of the river while ignoring conditions upstream.

How to analyse a system

There is no ultimate guide or right way to look at systems in the social sciences. Different people will define social systems differently depending on their perspective, power, goals and how they define the problem(s) they’re seeking to address.

Here’s what what we do know about systems that most experts agree on:

systems have a structure and a purpose (even if contested, hidden or unarticulated);

systems can be overlapping, nested and networked (think: your body);

systems include both official rules and unofficial norms, values and habits;

systems are influenced by their environment;

we can observe how they function, and we can often change how they function – something systems analysts like to think of in terms of ‘leverage points’.

Finally, there’s no one overarching ‘system’ to fight, fix, study or change when it comes to complex human problems and experiences. Only a conspiracy theorist would believe there’s a person behind the curtain pulling all the levers. But there are people and there is power. There are rules, norms, values, habits and goals. Things created by humans can be changed by humans (and we intervene in plenty of natural systems too).

The system as an ‘iceberg’

We like the Iceberg Model because it gives us a way of examining a system by its layers.

Source: https://ecochallenge.org/about/

On the surface is the ‘event’, the thing you can observe that you’re reacting to.

Underneath that are often patterns or trends, similar events taking place over time.

Below that, we have the ‘design’: the underlying structures influencing those patterns. Think of this layer as the relationship or connective tissue between the parts. This includes things like laws, rules and policies, so it’s where activists and policy experts tend to focus. It also includes our institutions, sometimes our physical structures.

But even that isn’t the final layer: at the base of all of it we have the “mental models” or the values, assumptions and beliefs; the paradigm that holds the system in place.

To apply this, let’s briefly take the problem of climate change:

Observable event: More frequent and ferocious fires, heatwaves and storms.

Patterns/trends: Global patterns and trends of hotter, dryer conditions and punctuated by stronger storms and floods.

Underlying structures: Humans generating energy from the burning of fossil fuels to power our homes, businesses, transport, food production and manufacturing creating a greenhouse effect. Economic and political systems, and human economic and social needs, that make it difficult to simply ‘switch off’ fossil fuel burning or compel all countries to cooperate on emission reduction agreements.

Mental models, values and beliefs, the paradigm: beliefs include include the assumption that nature exists for humans to use and dominate; that the purpose of people and nature is to serve the economy; that GDP growth is the priority goal of every government; that the needs of existing industry and business come before those of emerging industries; that government intervention or regulation are inherently bad; that it’s too hard or expensive to solve the problem globally; that technology will eventually make the problem go away; that humans will just have to ‘adapt’; there’s nothing we can do about it anyway; that it’s not really being caused by human activity; that I’ll be rejected by my peers if I do or say the wrong this in their eyes on this issue; that someone else will surely solve the problem; that if it’s too hard to solve it must not really be a problem at all; that it’s an issue for another day, year or decade to address; that God is in charge so we should just carry on.

The Iceberg Model further demonstrates how values and beliefs aren’t just a fuzzy-headed notion or a matter of political platitudes, something we ‘sprinkle over the top’ of our announcements and policies. They’re our foundation. They are the stories we tell ourselves about how the world works and should work. They help define the purpose, goals and rules of our systems; who systems benefit and punish and how we intervene in them, or not.

Where do we most usefully intervene to change a system?

There are, as you’d expect, entire bodies of literature devoted to this question.

Environmental scientist, educator, writer and one of the ‘founding mothers’ of systems thinking, Donella Meadows, lists the different levels to intervene in a system in order of effectiveness.

At the top of the leverage point – least effective but easiest to change – are things like subsidies, taxes and standards.

In the middle range are things like strengthening negative feedback loops and driving positive feedback loops, as well as changing the rules of the system with new incentives, punishments and constraints.

At the very foundation, the most effective but most difficult to leverage, are the goals of the system and the mindset or paradigm out of which the system arises.

We can see how her thinking is compatible with the Iceberg Model.

Assuming we don’t have the power, resources or capacity to intervene at every point in the system simultaneously, we can still look at the layers and ask: where does change need to happen and where am I/where are we best equipped to act?

For example, before marriage equality became the law of the land in the US, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) lobbied producers of the hit TV show Modern Family to create a same-sex marriage story line between two of the main characters.

Well before that, Hollywood cooperated with Harvard’s School of Public Health to introduce the notion of having a fun and responsible ‘designated driver’ to keep friends safe when they went out drinking. Both these interventions helped to change systems including social norms, values and expectations. It doesn’t happen always by laws and rarely, if ever, by laws alone.

There is also evidence from psychology that sometimes a change in rules or behaviour leads to a change in attitudes and beliefs, rather than the other way around.

Think about parenting: teaching children manners, respectful behaviour and giving them chores to do can help children to become more grateful, respectful and responsible; rather than waiting for them to feel grateful, respectful and responsible first, then giving them ways to express that. Focusing on persuasion isn’t always the best approach.

So, going back to our climate change example, we can ask:

Is the challenge still in shifting values, attitudes and beliefs?

Is the challenge in making our laws, policies, norms or practices catch up with the shift in our values, attitudes and beliefs?

Can we usefully change how we anticipate events, patterns and trends?

Can we usefully change how we respond to the events themselves, such as extreme weather events?

Assuming we could usefully intervene at multiple levels of the system, what work is ours to do specifically?

In other words, what needs to happen and where is our personal agency, capacity and influence? We can understand where our own strategic power or potential power is and intervene accordingly.

Looking ahead: building systems that are worthy of us

In his book Humankind: a hopeful history Dutch historian Rutger Bregman makes the case that despite world wars, atrocities and other disturbing events, human nature is basically good. People are wired for connection, cooperation and altruism. The evidence from famous psychological studies through to armed conflicts suggests that getting humans to do evil to one another generally requires convincing them that they are, in fact, doing good.

However, Bregman says, there’s a design flaw. We’ve set up our modern-day political and economic systems based on a faulty picture of negative assumptions about others: the idea that people are basically greedy, lazy, conniving, selfish and eager to take advantage wherever possible.

He argues that far from being merely prudent or ‘neutral’ in effect, this negative paradigm actively creates a kind of ‘nocebo’ or a negative self-fulfilling expectation; the opposite of the often-studied positive placebo effect. We expect the worst and we get it. From a systems perspective, it makes perfect sense. And Bregman is far from alone in pointing this out.

Part of our work, as reMAKERs is to make visible the different set of values that we do want to drive our systems, so we can go about better operationalising those values.

What would it look like to create economic, political and social systems that better reflected our values, and actively expected the best of people?

It’s a big question. As a piece of the answer, we’ve identified five key ‘Drivers of Transformation’ (the “Five Ds”), to help shift our systems to better support our vision for the best version of us. You can read more about the thinking behind these 5 Ds in our article, The Recovery Begins Now.

The Five Ds are: democratise, de-carbonise, de-monopolise, de-marketise and decolonise.

Perhaps you can see your own work or calling clearly reflected in one of these drivers. Certainly many of us are working across more than one of them.

Australia reMADE is currently focused on de-marketise and democratise in a project on reMAKING the public good; while we continue to think about, collaborate and support efforts across all five.

Onwards, with progress over perfection

Systems change does not equal perfect solutions. Silver bullets are very rare indeed.

Probably the biggest trap in thinking about how to change systems is overwhelm and paralysis.

All of this systems-change stuff can sound terribly intimidating and impossible, but it’s usually quite pedestrian, unsexy, behind-the-scenes sort of work. As David Ehrlichman writes, leverage points in a system can include,

“[C]reating policies to reduce national carbon emissions, rather than [just] building a higher and higher seawall. Providing young children with quality oral healthcare, rather than filling cavities later in life. Or expanding affordable housing and mental health resources, rather than opening a new homeless shelter.”

It’s natural to be intimidated when it comes to systemic solutions and systems-change. All the injustices we observe are interconnected and compounding. Nothing seems good enough, everything feels too big and too hard. We’ve written before about all the barriers to being more vision-led and bold in our work and in our lives:

“The problem is not that we’ve had organisations and individuals focused on stopping bad things, holding power to account and putting out fires. It’s that we’ve lacked an alternative story to share about how things can be, and big solutions to back it up that people believe in and are willing to try.” - “Mapping the Future we can Embrace” by Lilian Spencer, Australia reMADE

This is why everything we do as reMAKERs is grounded in vision, values and solutions. From our stories of reMAKING to reMAKER U and of course our vision itself, we understand that working for something is often less defined, slower, more vulnerable and behind-the-scenes than working against something. But if one is necessary, then so is the other.

Transcending paradigms, building new ones

Donella Meadows offers us one final clue: a level of change even more profound and effective than changing the goals, values or paradigms of a system. She calls it the ‘power to transcend paradigms’:

“There is yet one leverage point that is even higher than changing a paradigm. That is to keep oneself unattached in the arena of paradigms, to stay flexible, to realize that NO paradigm is ‘true,’ that every one, including the one that sweetly shapes your own worldview, is a tremendously limited understanding of an immense and amazing universe that is far beyond human comprehension. It is to ‘get’ at a gut level the paradigm that there are paradigms, and to see that that itself is a paradigm, and to regard that whole realization as devastatingly funny. It is to let go into Not Knowing, into what the Buddhists call enlightenment.

People who cling to paradigms (which means just about all of us) take one look at the spacious possibility that everything they think is guaranteed to be nonsense and pedal rapidly in the opposite direction. Surely there is no power, no control, no understanding, not even a reason for being, much less acting, in the notion or experience that there is no certainty in any worldview. But, in fact, everyone who has managed to entertain that idea, for a moment or for a lifetime, has found it to be the basis for radical empowerment. If no paradigm is right, you can choose whatever one will help to achieve your purpose. If you have no idea where to get a purpose, you can listen to the universe (or put in the name of your favorite deity here) and do his, her, its will, which is probably a lot better informed than your will.

It is in this space of mastery over paradigms that people throw off addictions, live in constant joy, bring down empires, get locked up or burned at the stake or crucified or shot, and have impacts that last for millennia.”

We hear this idea reflected more modestly in the advice to ‘stop fighting for a seat at the table and build a new table.’ We see it expressed in a favourite quote from Way of the Peaceful Warrior, “The secret to change is to focus your energy not on fighting the old, but on building the new.” We see it in great art, and in stories that show us who we can be.

Sometimes we’re stuck fighting inside and changing the systems we have. We can’t just go off and invent a new economic, legal, health or political system from scratch, which is why we seek to both unravel as we reMAKE. But we can’t forget to reMAKE! And to do so boldly and effectively we need to break free of a certain gravity or dogma; what Steve Jobs called, “the weight of other people’s thinking.”

Because this we know is true: those who ignite new stories and build new paradigms have the power to bring us all with them.

Reflection Questions

What is the purpose (including hidden, unarticulated or contested) of the system you’re seeking to change? If unsure, think about the mental models and beliefs that hold the system in place and perpetuate it (we do ‘X’ in order to achieve ‘Y’).

Where are the various leverage points in the system you’re seeking to change?

Which ones are most compelling, and which ones are most compelling for you as a reMAKER? Where are you more likely to be influential, strategic and effective?

-Can you intervene at the level of the observable phenomenon or event (‘react’)?

-Can you intervene to change patterns and trends (‘anticipate’)?

-Can you help to change laws, policies, norms or practices (‘design’)?

-Can you help to shift values, attitudes and beliefs (‘transform’)?

Are there any attempted interventions which haven’t worked yet, or backfired, etc?

-Which part(s) of the system were these interventions targeting?

-Which parts still needed to be addressed?

Lead Author Lilian Spencer, with the Australia reMADE team

Further Resources and recommended reading

There are entire bodies of literature devoted to systems theory and systems change from a range of disciplines, from cybernetics to ecology. Here are resources we’ve found helpful for social change.

Systems-change: a guide to what it is and how to do it for the social sector – including non-profits, governments and philanthropists, by the UK-based think tank and advisory group New Philanthropy Capital (NPC).

Leverage Points: Places to Intervene in a System by Donella Meadows.

Thinking in Systems: A primer by Donella Meadows.

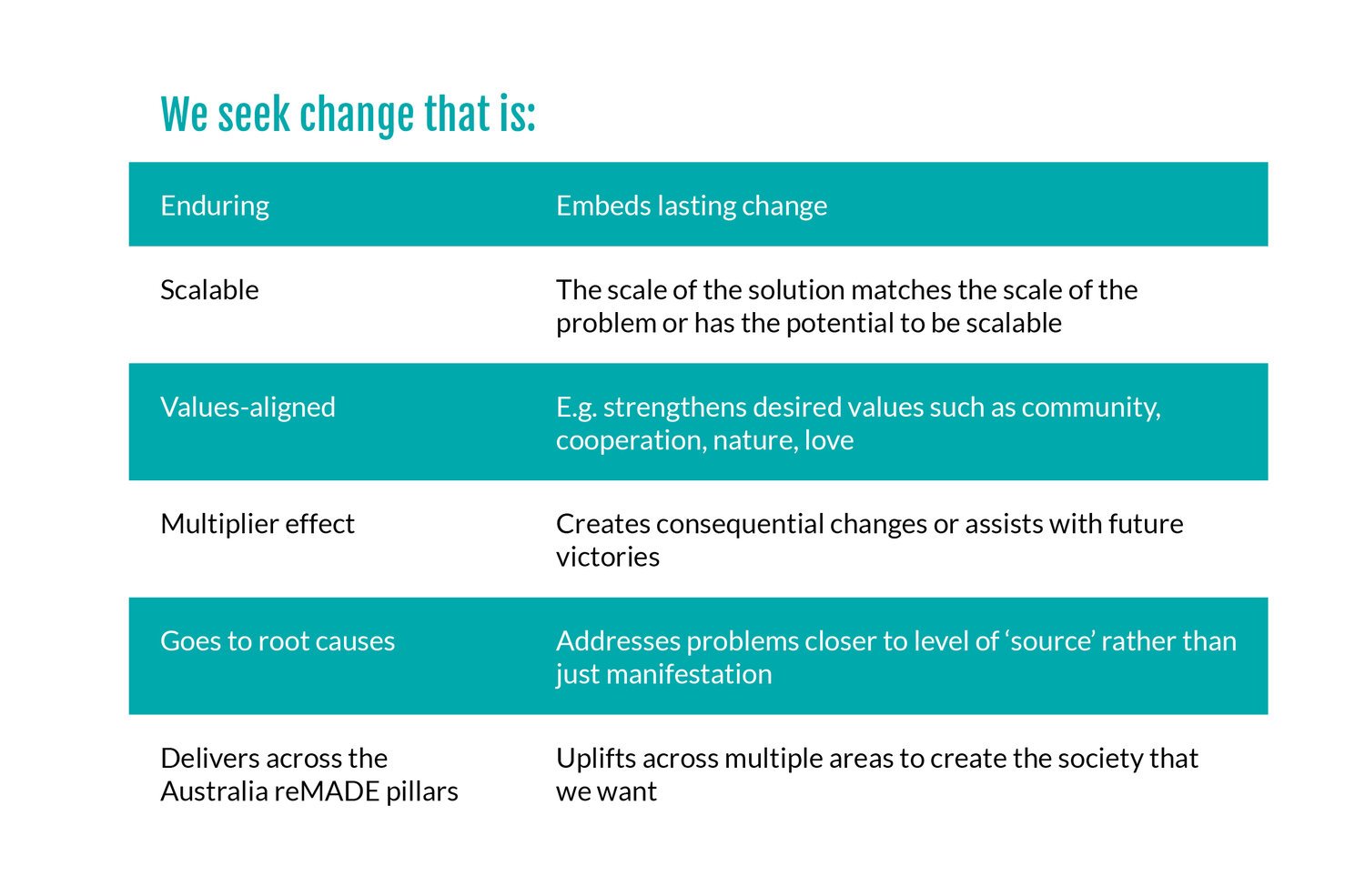

Criteria for Transformation two-page summary guide and PDF from Australia reMADE.

The Recovery Begins Now: a blog from Australia reMADE about how we’ll decide what the ‘new normal’ will look like.

‘Yes, And’ - A reMAKING in brief piece by Louise Tarrant for Australia reMADE about the pursuit of justice and ambition.